This post is also available in:

Indonesian

Indonesian

This is the third blog in our Women in Fisheries series.

Perched at a wobbly table in FORKANI’s workshop room, the floorboards above me creak and a yellow spider bearing black polka dots falls onto my arm. The skies outside are dark even though it is only mid-morning; torrential rain falls outside, cooling the air and dampening the noise from the village. But the gloom outside has not permeated FORKANI’s office. Over the many voices bursts the infectious laughter of Mursiati, known to everyone as Nusi.

Nusi first became involved with FORKANI in 2007 when she was invited to a training course in writing. She loved to write and had already produced articles for her university newsletter as a student, so she was eager to attend the course. After the training, she became involved in producing the newsletter of the four NGOs working in the Wakatobi Archipelago – FORKANI, FONEB, Komanangi and Komunto – to share information about their projects and educational messages about the environment, with communities throughout the region.

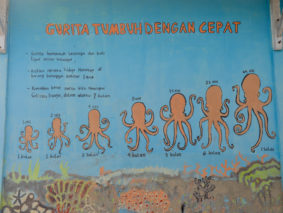

As the years have passed, Nusi’s role has diversified. “Now, I do everything!” she laughs. She is involved in many of the projects that FORKANI runs, including the fisheries management project on Darawa Island. She has led this project through many stages, beginning by educating the community about the life history of octopus – explaining their short life cycles and how a break from fishing pressure for just a few months can allow octopus to grown much bigger and fetch better prices. Following this, she trained women to collect data on octopus catches, and to present those data back to the community, so that they can better understand the state of the fishery.

Communication is key

The FORKANI team periodically receive the octopus catch data from their local data collectors, and have thought creatively about the many ways in which they can convey those data, once analysed, back to the fishing communities. They want the communities to understand the information they themselves have collected. With this kind of long-term dataset, fishers can see the changes in numbers and sizes of octopus over time – but only if the data are put together in a way that speaks to them.

Nusi is a colourful figure with apparently unlimited energy and good humour, and although she is involved in many elements of FORKANI’s work, communication is clearly her forte. She has been involved in developing creative ways to communicate the information about trends in octopus catches, in formats that are easy to digest and relevant to the community’s interests and concerns. She noted that FORKANI’s first attempts – using printed bar charts that resulted from the scientific analysis of their data – were not successful. Community members had little familiarity with bar charts or how to read them, and didn’t connect the abstract concepts of catch rates with their daily lives.

“These are your data. Your octopus.”

FORKANI have since tried presenting catch data in the form of its financial value to fishers, and using different visual formats such as brightly coloured styrofoam models of octopus and large sheets of paper decorated with underwater scenes. Each time Nusi presents the data, she reiterates that they belong to the community and are there to enable them to make decisions about their own fisheries. “The first thing I tell the community when I present the data, is ‘these are your data, these are YOUR octopus’ – so they really begin to develop ownership of the information they collect. We think this is important because people have seen research before, but they never saw the results of that research”.

Nusi also puts the management efforts of the Darawa community into a broader context by sharing the activities and experiences of other communities, such as those in Madagascar, who are also managing their own fisheries and coastal environments. In the short film ‘Opening’, Nusi explains the work FORKANI has done with the community of Darawa, and the creative and energetic way in which she engages with the community to explain the fisheries data to them is evident.

Building confidence in community and culture

Photo: Claudia Matzdorf

For Nusi, the best part of her work in Darawa is seeing community members discussing their own resources. “I have seen a real empowerment amongst people who previously felt that they had no rights to manage their own resources. They now have the confidence to take initiative within the community, and even to engage with local government authorities to discuss management issues”, she notes.

The FORKANI team has a long-term vision for the communities in which they work. They see temporary octopus fishery closures exactly as they were intended – not as the end-goal, but as the starting point along the long road to community-based natural resource management. “What we’re doing now is just the beginning of communities managing their own natural resources, at a small-scale. We hope in future communities in Wakatobi can sit together and having started with octopus, discuss where to go – think about other resources.”

I have seen a real empowerment amongst people who previously felt that they had no rights to manage their own resources. They now have the confidence to take initiative within the community, and even to engage with local government authorities to discuss management issues”

There never seems to be a conversation where Nusi doesn’t erupt into fits of laughter or make a joke about another FORKANI team member. “Yanti and I make a good team”, she says mischievously. “I’m loud and everyone tells me I speak too quickly, but Yanti is calm, she speaks slowly and she is so organised!”. I see this formidable team in action when I accompany them to Darawa a few days later. As we walk the narrow pathways, spread with the crimson hues of drying seaweed, Yanti and Nusi are greeted warmly, like old friends, by the people we pass. Nusi jokes with some, waves and calls out to others in their houses, whilst Yanti goes to find the female data collectors to get updates on their work. Watching the two of them engaging with the community, I can see that their work with FORKANI is widely respected and yet, it has not been easy for either of them to remain as part of the FORKANI team.

“We need more ideas, more perspectives – we need new women to get involved!”

Nusi was the second woman to join FORKANI, at a time when it was socially unacceptable for women to be involved in the kind of work she does. Even now, there are very few women actively involved in environmental work in Wakatobi – Nusi estimates about ten in total. “We need more ideas, more perspectives – we need new women to get involved!”, she says. I ask her whether she has any words of advice for younger women wanting to get involved in fisheries management, and follow the less-than-conventional trail she has blazed. Her response, as always, cuts to the chase.

God created us all as humans. Never say that a woman cannot do something because she is a woman. Women can do anything they are passionate about, just the same as men”.

Read more from our Women in Fisheries series: